Mixing Mechanisms: How Language Models Retrieve Bound Entities In-Context

To reason, LMs must bind together entities in-context. How they do this is more complicated than was first thought.

TL;DR: Entity binding in LMs is crucial for reasoning in LMs. Prior work established a positional mechanism underlying binding, but we find that it breaks down in complex settings. We uncover two additional mechanisms—lexical and reflexive—that drive model behavior.

Jump to the interactive demo below, or read the full paper here.

Introduction

Language models (LMs) are known for their ability to perform in-context reasoning, and fundamental to this capability is the task of connecting related entities in a text—known as binding—to construct a representation of context that can be queried for next token prediction. For example, to represent the text Pete loves jam and Ann loves pie, an LM will bind Pete to jam and Ann to pie. This enables the LM to answer questions like Who loves pie? by querying the bound entities to retrieve the answer (Ann). The prevailing view is that LMs retrieve bound entities using a positional mechanism

However, we show that the positional mechanism becomes unreliable for middle positions in long lists of entity groups, echoing the lost-in-the-middle effect

In this post we describe exactly how LMs use the positional, lexical and reflexive mechanisms for entity binding and retrieval, which we validate across (1) nine models from the Llama, Gemma and Qwen model families (2-72B parameters), and (2) ten different binding tasks. These mechanisms and their interactions remain consistent across all of these, establishing a general account of how LMs bind and retrieve entities.

Three Mechanisms For Binding and Retrieval

The prevailing view is that entities are bound and retrieved with a positional mechanism

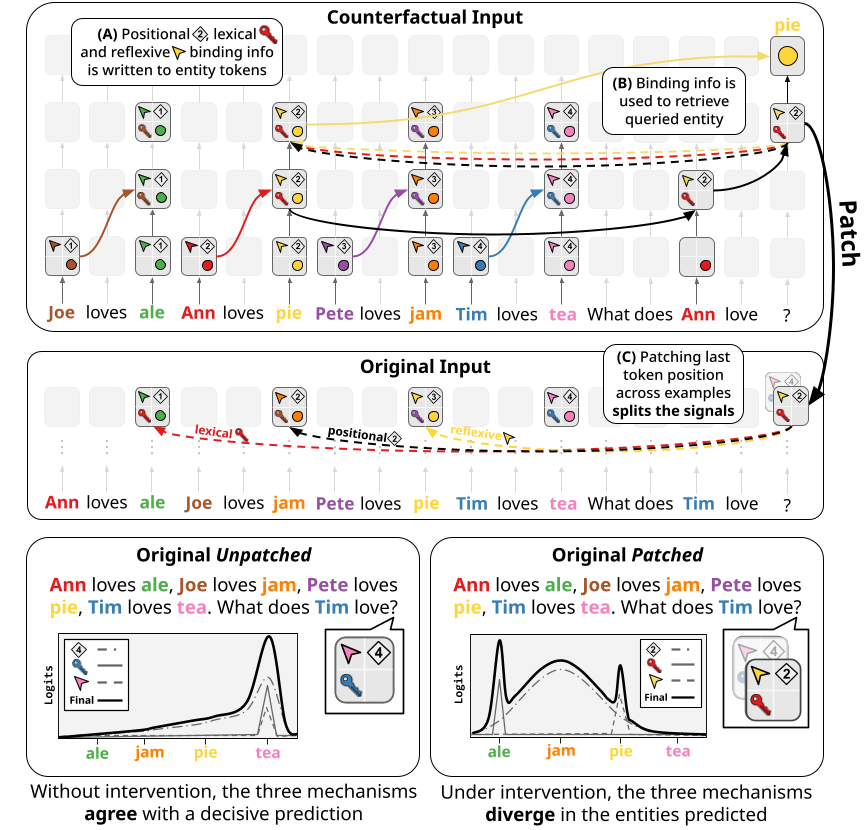

- Positional - given a query entity (What does Tim love?), the model extracts the index of the entity group to which it belongs (4), and retrieves the queried entity (tea) from it. Thus, patching this binding information from the counterfactual (where the queried entity group index is 2) to the original would make the model respond with the answer from entity group number 2 (jam).

- Lexical - where instead of using the position of the query entity, the model uses its lexical content to retrieve the bound entity from the group containing the query entity. This is achieved by copying the lexical contents of the Tim token into the tea token position (illustrated in Figure 2 with a key), which can then trigger the attention of the query token (Tim), enabling retrieval of the bound entity (tea). Thus, patching in this binding information from the counterfactual (where the query entity is Ann) to the original would make the model respond with the answer from the entity group with Ann (ale).

- Reflexive - where each entity in an entity group also encodes a pointer that points directly to itself, which can then by copied to other entities in its entity group and dereferenced in order to retrieve its originating entity. This mechanism is needed because the lexical mechanism, as described previously, requires information being copied between entity tokens to bind them together. However, if we query the first token in an entity group (i.e. Who loves tea?), then this mechanism would be useless, since the causal attention mask forbids the lexical contents of tea being copied backward to Tim. Thus, reflexive binding information pointing to Tim and originating from it, is copied forward to the tea token position, which can then be retrieved using the query entity (Who loves tea?), and used to retrieve Tim. Thus, in Figure 2, patching in this binding information from the counterfactual (where the answer entity is pie) to the original would make the model respond with pie. Note that this behavior is identical to patching in the answer itself from the counterfactual to the original, but we disambiguate these two mechanisms in multiple subsequent experiments involving more elaborate datasets as well as attention knockouts

, confirming the existence of this mechanism. Note also that this binding information only points to the token from which it originated (using its lexical content). Therefore, patching this binding information to a prompt where the pie entity doesn’t exist would lead to the model not being able to use this mechanism for retrieval.

Results and Analyses

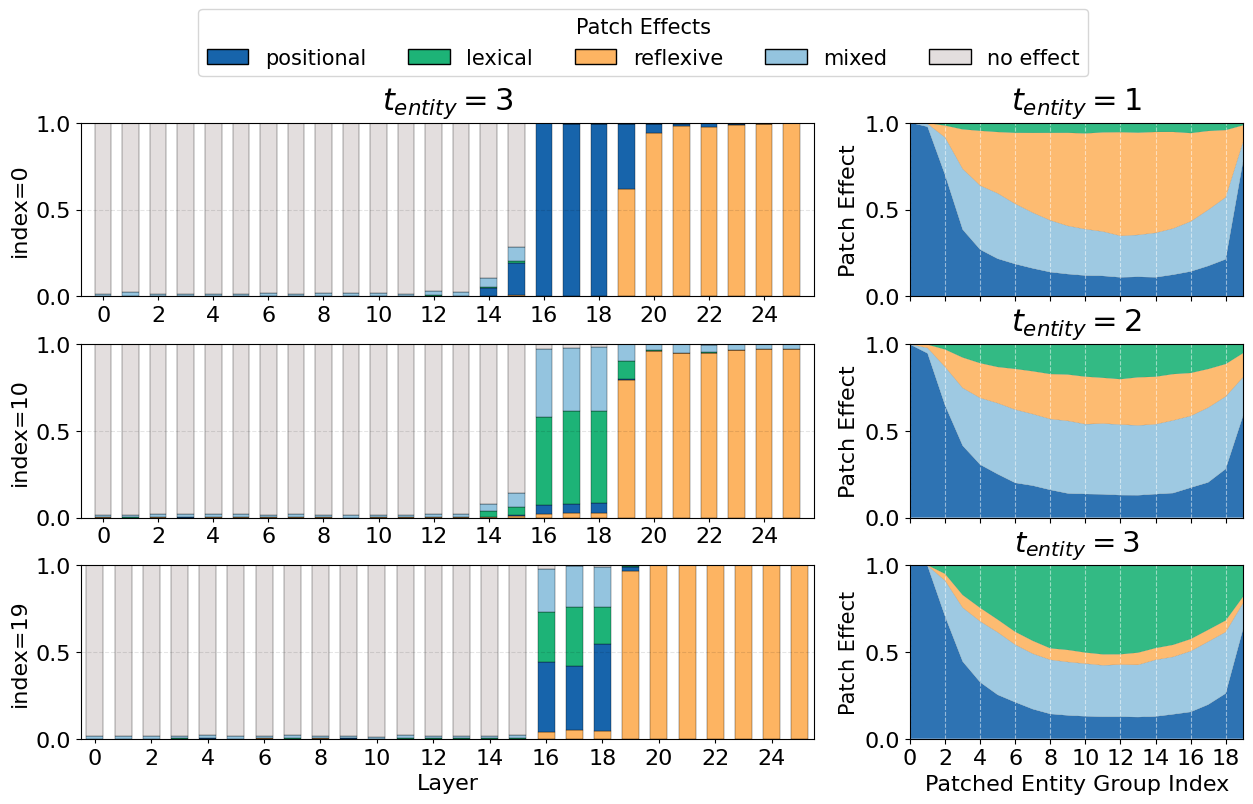

In Figure 3, we see the results of our interchange interventions for gemma-2-2b-it (replicated for all other models in the paper). We also collect the mean output probabilities for each possible answer entity post patching, highlighting the entities pointed to by each of the mechanisms, to understand the interplay between the three mechanisms.

Aggregating Binding Information

We see in Figure 3 that in layers 0-15, no binding information exists in the last token position, since patching it doesn’t have any effect on model behavior. In layers 19-25, the model has already retrieved the bound entity, since patching the last token position leads to the model responding with the answer from the counterfactual example. However, in layers 16-18 we see that the model has aggregated the binding information in the last token position, since patching it from the counterfactual to the original leads the model to respond with entities corresponding to the positional, lexical and reflexive mechanisms.

The Positional Mechanism is Weak and Diffuse in Middle Positions

Figure 3 shows that the positional mechanism controls model behavior only when querying the first few and last entity groups. In middle entity groups, however, its effect becomes minimal, only accounting for ~20% of model behavior.

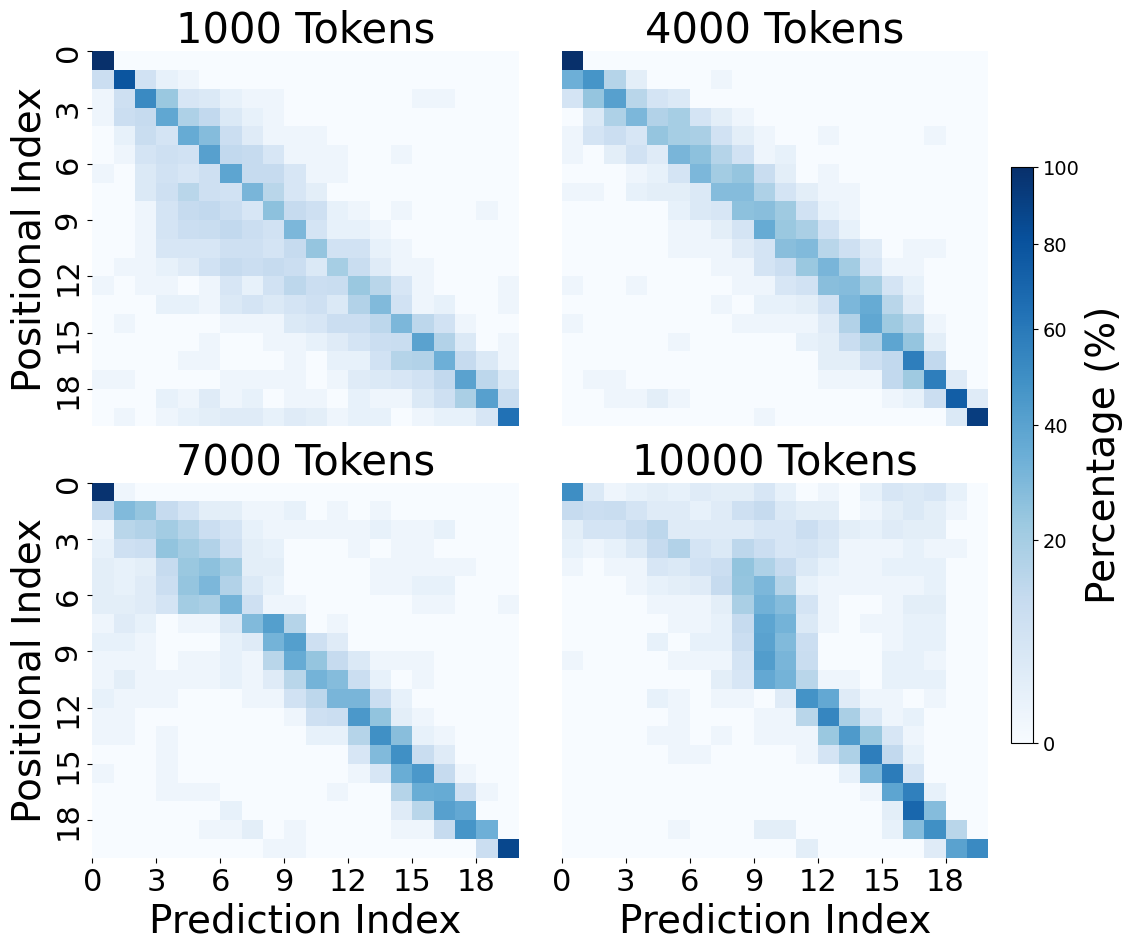

In Figure 4 we see the mean probabilities for each answer entity (in order of their entity group index, i.e. in order of appearance in context), fixing the lexical and reflexive mechanisms to point to the first entity, and sliding the positional mechanism across all values. We see that the mechanism induces a strong concentrated distribution around the entity pointed to by the positional mechanism in the beginning and end, but that in middle entity groups its distribution becomes weak and diffuse. This indicates that the model struggles to use positional information to bind together entities in middle entity groups, making it unreliable as the sole mechanism for binding.

Interplay Between The Mechanisms

We see in Figure 5 that, contrary to the positional mechanism, the lexical and reflexive mechanisms induce one-hot distributions at their target entities. The distributions induced by the three mechanisms then interact with each other in shaping the model’s behavior, both boosting and suppressing each other. We see for example that when the lexical / reflexive mechanisms point at entities near the positional one, their probabilities increase dramatically, while simultaneously suppressing that of the entity pointed to by the positional mechanism.

A Simple Model for Simulating Entity Retrieval In-Context

To formalize out observations about the dynamics between the three mechanisms and the position of the queried entity, we develop a high-level causal model

Where $i_{P/L/R}$ are the entity group indices pointed by the positional, lexical and reflexive mechanisms respectively, and $\sigma(i_P) = \alpha (\frac{i_P}{n})^2 + \beta \frac{i_P}{n} + \gamma$. We learn $w_{pos},w_{lex},w_{ref},\alpha, \beta, \gamma$ from data.

To train and evaluate our model, we collect the logit distributions per index combination, and average them into mean probability distributions by first applying a softmax over the entity group indices, and then taking the mean. We calculate the loss using Jensen-Shannon divergence (chosen for its symmetry), and measure performance using Jensen-Shannon similarity (JSS), its complement, which ranges from 0 to 1. We also compare our model to the prevailing view (one-hot distribution at $i_P$), as well as various ablations of our model. Finally, we compare our model to an oracle variant, an upper bound where we replace the learned gaussian with the actual collected probabilities.

| Model | JSS ↑ $(t_e=1)$ | JSS ↑ $(t_e=2)$ | JSS ↑ $(t_e=3)$ |

|---|---|---|---|

| Comparing against the prevailing view | |||

| $\mathcal{M}(L_{\text{one-hot}}, R_{\text{one-hot}}, P_{\text{Gauss}})$ | 0.95 | 0.96 | 0.94 |

| $\mathcal{P}_{\text{one-hot}}$ (prevailing view) | 0.42 | 0.46 | 0.45 |

| Modifying the positional mechanism | |||

| $\mathcal{M}$ w/ $P_{\text{oracle}}$ | 0.96 | 0.98 | 0.96 |

| $\mathcal{M}$ w/ $P_{\text{one-hot}}$ | 0.86 | 0.85 | 0.85 |

| Ablating the three mechanisms | |||

| $\mathcal{M} \setminus \{P_{\text{Gauss}}\}$ | 0.67 | 0.68 | 0.67 |

| $\mathcal{M} \setminus \{L_{\text{one-hot}}\}$ | 0.94 | 0.91 | 0.75 |

| $\mathcal{M} \setminus \{R_{\text{one-hot}}\}$ | 0.69 | 0.87 | 0.92 |

| $\mathcal{M} \setminus \{R_{\text{one-hot}}, L_{\text{one-hot}}\}$ | 0.69 | 0.84 | 0.74 |

| $\mathcal{M} \setminus \{P_{\text{Gauss}}, R_{\text{one-hot}}\}$ | 0.12 | 0.27 | 0.48 |

| $\mathcal{M} \setminus \{P_{\text{Gauss}}, L_{\text{one-hot}}\}$ | 0.55 | 0.41 | 0.20 |

| Uniform | 0.44 | 0.57 | 0.49 |

We see in Table 1 that our model achieves near perfect results (0.95), only slightly below the oracle variant (0.97). We also see that the model representing the prevailing view achieves much worse results (0.44), well below even a uniform distribution (0.5). Finally, we can see when each component of our model is important for modeling the LM’s behavior: when querying the first entity in a group, the lexical mechanism is not crucial for modeling the LM’s behavior, while when querying the last entity the reflexive one isn’t, in line with our hypothesis.

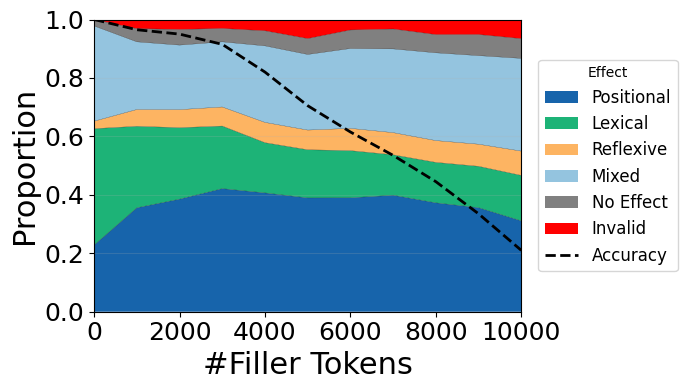

Introducing Free Form Text Into the Task

To test our model’s generalization to more realistic inputs, we modify our binding tasks such that they include filler sentences between each entity group. To this end, we create 1,000 filler sentences that are “entity-less”, meaning they do not contain sequences that signal the need to track or bind entities, e.g. “Ann loves ale, this is a known fact, Joe loves jam, this logic is easy to follow…”. This enables us to evaluate entity binding in a more naturalistic setting, containing much more noise and longer sequences. We evaluate different levels of padding by interleaving the entity groups with an increasing number of filler sentences, for a maximum of 500 tokens between each entity group.

The results, shown in Figure 6 and 7, show that our model at first remains remarkably consistent in more naturalistic settings, across even a ten-fold increase in the number of tokens. However, as the amount of filler tokens increases, we see that the magnitude of the mechanisms’ effects changes. The lexical mechanism declines in its effect, while the positional and mixed effects slightly increase. We can also see that the mixed effect remains distributed around the positional index, but that it slowly becomes more diffuse. Thus, when padding with 10,000 tokens, we get that other than the first entity group, the positional information becomes nearly non-existent for the first half of entity tokens, while remaining stronger in the latter half. This suggests that a weakening lexical mechanism relative to an increasingly noisy positional mechanism might be a mechanistic explanation of the “lost-in-the-middle” effect

Conclusion

In our work, we challenge the prevailing view that LMs retrieve bound entities purely with a positional mechanism. We find that while the positional mechanism is effective for entities introduced at the beginning or end of context, it becomes diffuse and unreliable in the middle. We show that in practice, LMs rely on a mixture of three mechanisms: positional, lexical, and reflexive. The lexical and reflexive mechanisms provide sharper signals that enable the model to correctly bind and retrieve entities throughout. We validate our findings across 9 models ranging from 2B to 72B parameters, and 10 binding tasks, establishing a general account of how LMs retrieve bound entities.

Interactive Figure

Here we provide an interactive figure, showing the mean output probabilities (gemma-2-2b-it) over the possible answer entities contingent on which entities are pointed to by the positional, lexical and reflexive mechanisms (pos, lex and ref respectively). You can control the number of entity groups in the context (n), as well as which entity in a group is queried (target). See the full blog post or our paper to understand more about how LMs perform binding and retrieval.

Please cite as:

@misc{gurarieh2025mixing,

title={Mixing Mechanisms: How Language Models Retrieve Bound Entities In-Context},

author={Yoav Gur-Arieh and Mor Geva and Atticus Geiger},

year={2025},

eprint={2510.06182},

archivePrefix={arXiv},

primaryClass={cs.CL}

}